Unveiling the World's Oldest Known Monastery

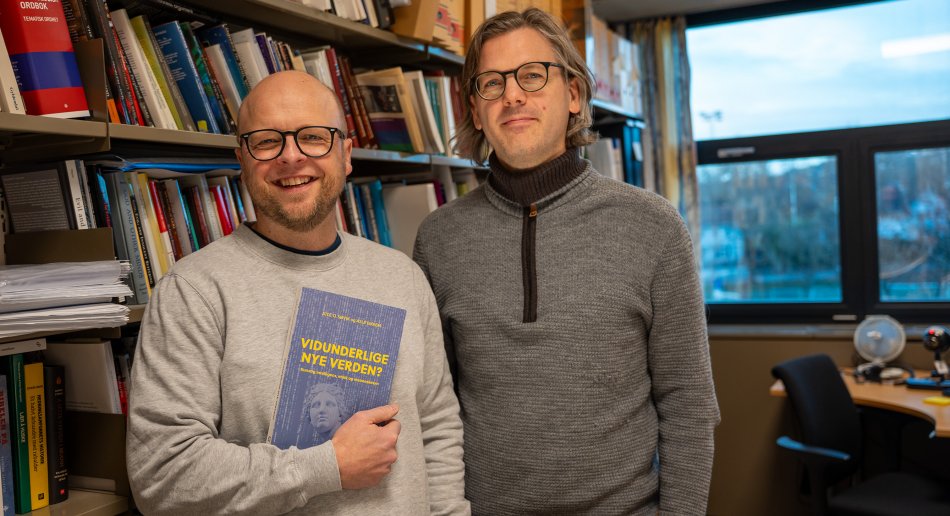

MF Prof. Victor Ghica Reveals the Finds of his dig at Tall Ğanūb Qaṣr al-‘Ağūz.

Monasticism is a religious way of life wherein adherents withdraw from society and opt for seclusion in search of spiritual enlightenment. In its institutionalised form, the practice originated in fourth century Egypt, where many followers of the fast-spreading Christianity were enticed by the endless deserts, which provided opportune environments for isolated, or at least semi-isolated, religious communities. The site of Tall Ğanūb Qaṣr al-‘Ağūz, or simply ‘GQA’, is one of a number of such communities mentioned in the ancient written sources. It is unique, however, in that it is perhaps the oldest archaeologically attested monastic site, not only in Egypt, but in the world.

Based on stratigraphy, radiocarbon analysis, ceramic and glass assemblages and coins, the foundation date of the earliest stage of this federation of hermitages can be situated around the first half of the fourth century, making it the oldest preserved Christian monastic site that has so-far been dated with certainty. The site has seen three seasons of excavation directed by Prof. Victor Ghica, in partnership with the Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale (IFAO) and MF Vitenskapelig Høyskole, Norway. Despite the current state of the world in light of Covid-19, the most recent of the three excavation seasons was December 2020.

Located some 370km south-west of Cairo in the Baḥariya Oasis, the site consists of six sectors constructed predominantly of basalt blocks and mud. Also included are a number of buildings which are dug partially, or completely, in the bed-rock. The layout of the buildings in each of these sectors, as well as the construction techniques employed, all of which include food preparation areas and living quarters, indicate that GQA operated as an atypical laura, that is, a semi-independent type of monastic setting comprising clusters of living spaces for monks.

The closest Roman period archaeological sites are between 2.4 and 3.8km away, making the site somewhat isolated when compared with typical Roman areas of habitation. It is this isolation, as well as the organisation of the internal areas of each sector, the presence of three churches, and countless graffiti and dipinti on the walls in sectors 1 and 6, which indicate the monastic nature of the community that lived here. In addition, the 2020 season brought to light a number of Greek ostraca which make reference to monks. The only archaeological or architectural parallel found so far is in the earliest structures of Kellia, located in the Nitrian Desert, the remnants of which have since disappeared.

The dig reveals a new face of the beginnings of organised Egyptian monasticism. The edges of Egypt are at the centre of the archaeology of the earliest Egyptian monasticism.

Prof. Victor Ghica

Four of the six buildings complexes that compose the site were found in an exceptional state of preservation, with all the walls intact, several roofs discovered in situ during the excavations and two rooms built on two floors. Although each of the sectors of GQA have seen destruction and vandalism, most of the structures and features are untouched, providing a wealth of information. For example, the walls of four of the rooms of GQA6, the area of focus for the 2020 season, including the walls of the church, are completely covered with religious texts written in Greek, including a passage from Evagrius and another one from Ephrem the Syrian’s Sermo asceticus.

It was revealed that a fifth room was similarly covered, but these texts are hidden beneath an additional layer of plaster. The removal of a limited amount of this plaster revealed that these texts are also of a religious nature. Most of this top-coat remains in situ, meaning the texts will stay protected from the elements and thus preserved until they can be studied properly at a later date. The limited ceramic from this sector studied in the previous seasons dates from the fifth and early sixth centuries. The ceramic from this season has not yet been studied, however, as the team’s ceramicist contracted Covid right before the mission commenced. Numerous organic samples were taken in order to better understand the chronology of the construction phases.

The fourth-century date mentioned derives for the time being from GQA1, the largest sector of the site, which saw five phases of construction. Based on stratigraphy, radiocarbon analysis, ceramic and glass assemblages and two coins, the foundation date of the sector can be situated in the mid-fourth, or even in the first half of the fourth century, making it the oldest preserved Christian monastic site that has been dated with certainty. Additional dating is underway to establish a more secure chronology of the sector, but so far, the available data indicates that this is the oldest preserved monastic site.

Most of the ceramic from GQA dates from the end of forth-early fifth century to the early sixth century, indicating that this was likely the peak of activity, at least in the sectors GQA1, 2, 3 and 6, while traces of later occupation, dating from the seventh to eighth centuries, have also been identified in GQA1, 2 and 6, probably correlating with the pastoralist re-occupation of the site. While the fourth century foundation date of GQA1 is just one of many remarkable features of this site, it is perhaps the most important, opening new perspectives for the study of the earliest stages of the monastic movement.

Aktuelt Forskning