The Role of Orientalism in the History of the Qurʿān

Do you know how the first English translation of the Qurʿān directly from Arabic came to be? It’s a fascinating result of a race between the Protestant and Catholic churches. Zeshan Ullah Qureshi explores how sharp polemics, impressive philology, and Christian rivalry have shaped both Europe’s encounter with the Qurʿān and European thought itself.

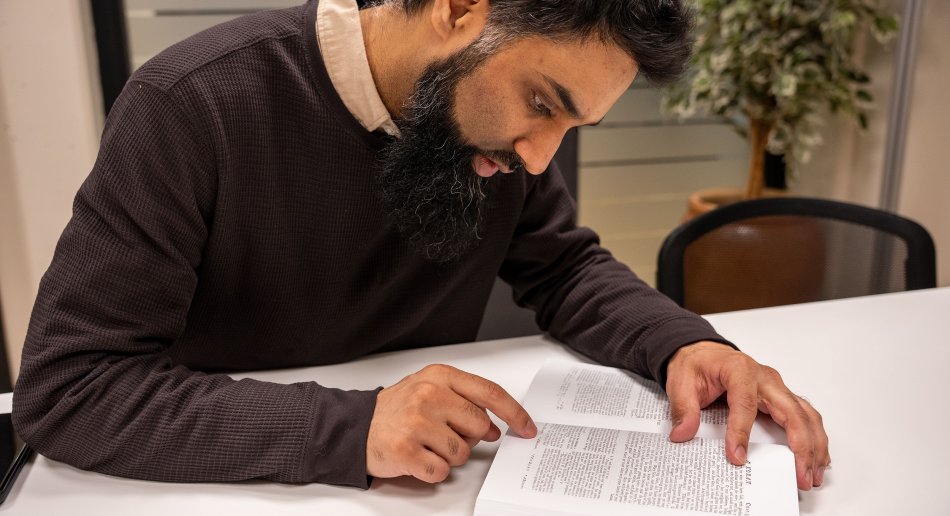

To understand Qureshi’s project, we must take a journey through the history of the Qurʿān in Europe. – I’m particularly interested in the historical cultural encounter between Europe and Muslims, intellectual history, and Islamic law, says Qureshi.

The first European translations of the Qurʿān were in Latin, with the first completed in Spain in 1143 by Robert of Ketton, intended as a tool in the effort to convert Muslims to Christianity. From this region, there are multiple translations throughout the medieval period due to access to Qurʿānic manuscripts, tafsīr literature, and Muslims living under Christian rule in Spain after the Reconquista. A classical tafsīr is a commentary on the Qurʿānic text, often word by word, that both explains and clarifies the historical circumstances behind specific revelations[1].

Qureshi’s doctoral project, “Beyond Orientalism: George Sale, al-Bayḍāwī, and the European Qurʾān Translation Tradition”, is affiliated with the ERC-funded project The European Qur’an (EuQu).

Jan Loop, Principal Investigator at EuQu, is Qureshi’s external supervisor, while Matthew Monger from MF is his main supervisor.

A Race Between Church Traditions

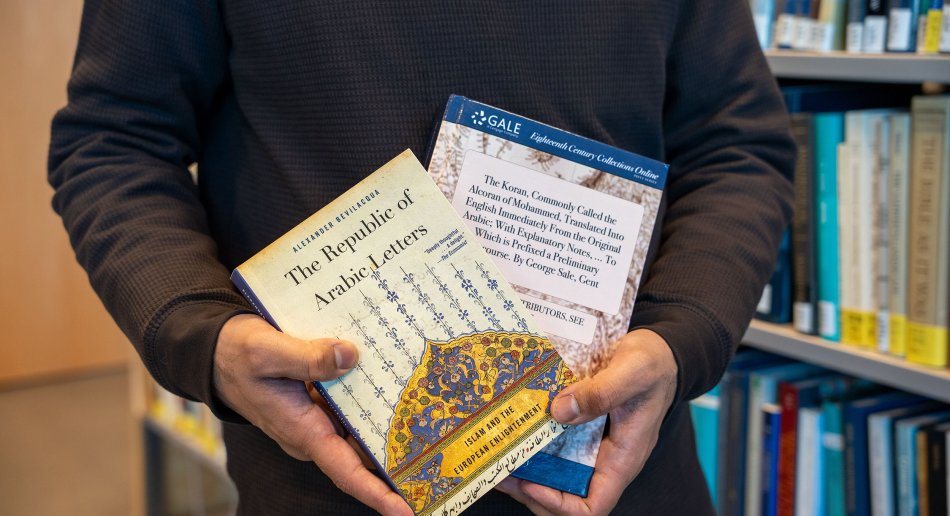

After Martin Luther became involved in the publication of a revised edition of Robert of Ketton’s translation, the Qurʿān was printed in a Western language for the first time in 1543. One of the conditions for publication was that Luther write a preface, where he stated that one of the purposes of the publication was to understand and refute the texts. This initiated a race between the Catholic and Protestant traditions to translate the Qurʿān.

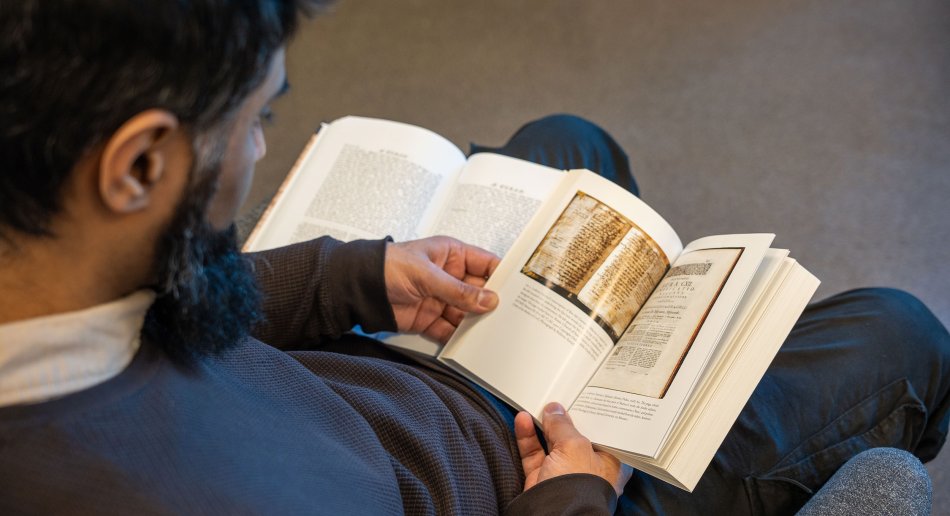

The most well-known Catholic translation came from Ludovico Marracci, who in 1698 published his version of the Qurʿān in Arabic, with Latin commentary and translation. Marracci had access to a large selection of tafsīrs through the Vatican Library. This is where Qureshi’s project comes in. In 1734, George Sale, a British orientalist, published the first direct translation of the Qurʿān into English. Sale’s version was based on Marracci’s 1698 edition and the tafsīr of the medieval theologian al-Baydāwī.

– Sale only had direct access to al-Baydāwī’s tafsīr. He gives the impression that he had access to other tafsīrs, but he didn’t. He relied on Marracci’s Latin translation, since he was in London and did not have access to the Vatican Library, explains Qureshi.

In his PhD project, Qureshi analyzes how Sale used al-Baydāwī’s tafsīr to produce the first direct English translation of the Qurʿān.

– It’s very interesting — you can see al-Baydāwī’s name in the footnotes on almost every single page. He refers to him 763 times in the translation, Qureshi points out. There are several critical editions of this tafsīr, in addition to many manuscripts.

– It was the most widespread tafsīr in the Muslim world until about 80 years ago, so it’s no surprise it made its way to England, says Qureshi.

Qureshi will examine the manuscript of al-Baydāwī’s tafsīr that Sale used, to understand what issues Sale aimed to address. This manuscript is now held in The London Archives.

– Everything does not necessarily make sense in the critical editions, but it may make sense in light of the manuscript, and that’s really interesting to explore, Qureshi notes.

– What does he use it for? Is there a pattern, or is it random usage? Or does he use al-Baydāwī to support specific arguments? That’s what the project is about, says Qureshi.

Everything does not necessarily make sense in the critical editions, but it may make sense in light of the manuscript

Zeshan Ullah Qureshi

The Book That Inspired

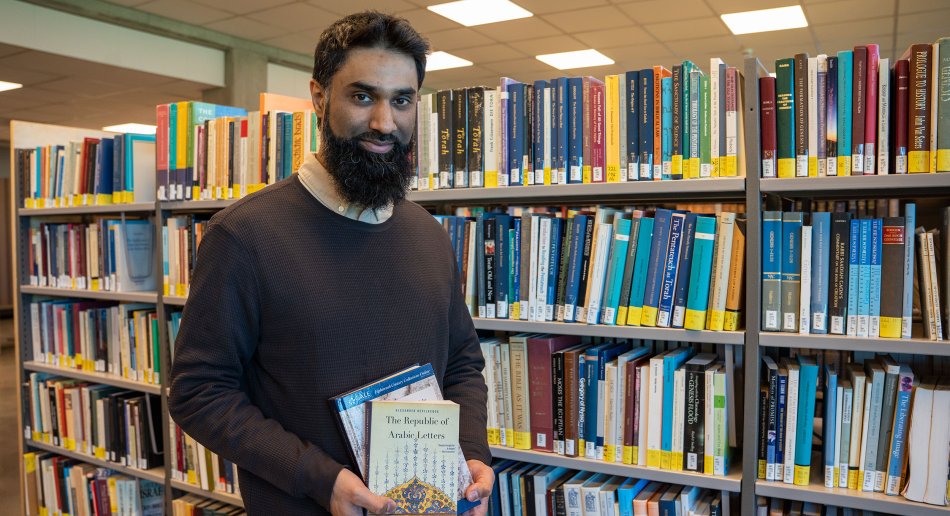

The idea for the project stems both from an interest in intellectual history and cultural encounters, as well as the book The Republic of Arabic Letters by Alexander Bevilacqua. The book is based on his doctoral research and deals with Islam and the European Enlightenment.

– I’d had the book for many years without reading it, but I started reading it after I came back to Norway. I didn’t get very far before Marracci’s and Sale’s translations were mentioned. Bevilacqua noted that Sale based his translation on al-Baydāwī, and that’s when I realized this could be an entire doctoral project. If someone could base an entire translation on a tafsīr, then analyzing all the corresponding verses in al-Baydāwī’s tafsīr is a whole project in itself,” Qureshi explains.

Early Observations

Qureshi is still in the planning phase of his project but has already discovered something that stimulated his interest.

– I’ve looked at the footnotes to see which references Sale uses, and I discovered that he also refers to many orientalists and Bible verses. Another observation I need to check in the manuscript is that in chapter two — the longest chapter in the entire Qurʿān — al-Baydāwī is only referenced once, Qureshi points out. Why does he refer to al-Baydāwī only once here, when he does that so many times throughout the rest of the translation, he wonders.

Some of Qureshi’s preliminary theories are that the manuscript in England may be missing chapter two, or that Sale had already completed the chapter using Marracci’s translation before gaining access to al-Baydāwī’s manuscript. These are questions not easily answered without looking at the manuscript, and perhaps Qureshi can shed more light on this as he comes close to the end of his project.

Qureshi is currently a PhD fellow in Religious Studies at MF Norwegian School of Theology, Religion and Society, though that wasn’t always the plan. He holds a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from Oslo Metropolitan University but chose to start over with a bachelor’s in Islamic law (sharīʿa) and followed up with a master’s in Islamic legal theory, both from the Islamic University of Madinah. After ten years in Saudi Arabia and Egypt, he has returned to Norway to delve into the role of Christian orientalists in translating the Qurʿān and their use of tafsīr.

[1] Vogt, Kari: tafsir in Store norske leksikon at snl.no. Retrieved April 2nd 2025 from https://snl.no/tafsir